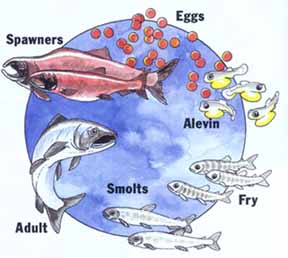

Commercial, Tribal, and sport fisheries depend on healthy populations of steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), coho salmon (O. kisutch), and Chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha). The following sections describe the habitat requirements and life histories of these fish species. The Trinity River Restoration Program considers these life histories and habitat requirements in planning, design, implementation, and monitoring activities.The life histories of anadromous species have two distinct phases, one in freshwater and the other in salt water. Newly hatched young remain in the river of their birth for months to years before migrating to the ocean to grow to their adult size. Adult salmonids return from the ocean to their natal rivers to spawn. Although steelhead, coho salmon, and Chinook salmon require similar instream habitats for spawning, egg incubation, and rearing, the timing of their life history events varies (see figure below).

GENERAL HABITAT REQUIREMENTS AND LIFE HISTORIES

Returning to the river for spawning

Anadromous adult salmonids enter the river from the ocean and hold until they are ready to spawn. Some species, such as spring-run Chinook and summer steelhead, enter the river months prior to spawning; these fish hold in deep pools for protection from predators and for cool thermal refuge during the summer. Once spawning begins, salmonids construct redds (spawning areas) in gravel. Continued... After hatching, the sac fry remain within the gravel interstitial spaces for four to ten weeks to avoid predation and dislodgement by high flows. Continued... During the next life-history stage, the juvenile or “parr” stage, juveniles spend from several months to 3 years growing in freshwater, depending on the species. Continued... On reaching a species-specific size, juvenile salmonids undergo smolting, a physiological metamorphosis that prepares them for outmigration from the river and for growth and survival in the ocean. Continued... The rate at which a smolt migrates out of the river is related to smolt size, flows, temperature, and photoperiod. Increasing streamflows and increasing water temperatures tends to increase the rate of smolt migration. The rate of smolt movement also increases from early in the season to late in the season as temperatures rise and photoperiod lengthens. Depending on species, adults typically return to their natal streams to spawn at 3 to 6 years of age. Some salmon return at 2 years of age and are referred to as “jacks”. Although jacks are capable of spawning, most are male and do not contribute to the production potential of the spawning escapement. Steelhead, unlike salmon, do not always die after spawning, and may make three to four spawning migrations. Each salmonid species requires slightly different microhabitats for each life stage and similar microhabitats are used by different species at different times of the year. This segregation of timing and microhabitats reduces competition between species. The life histories of each species are outlined above (see figure), with descriptions of the habitat components and lifestage timing critical to the growth and survival of each species. Continued... Chinook salmon are the largest Pacific salmon. Trinity River Chinook salmon populations are composed of two races, spring-run and fall-run. Spring-run Chinook salmon ascend the river from April through September, with most fish arriving at the reach below Lewiston (River Mile 111.9) by the end of July. These fish remain in deep pools until the onset of the spawning season, which typically begins the third week of September, peaks in October, and continues through November. The fall-run Chinook salmon migration begins in August and continues into December. Fall-run Chinook salmon begin spawning in mid-October, activity peaks in November, and continues through December. The first spawning activity usually occurs just downstream from Lewiston Dam. As the spawning season progresses into November, spawning extends downstream as far as the Hoopa Valley. Emergence of spring- and fall-run Chinook salmon fry begins in December and continues into mid-April. Juvenile Chinook salmon typically leave the Basin (outmigrate) after a few months of growth in the Trinity River. Outmigration from the upper river, as indicated by monitoring near Junction City (RM 79), begins in March and peaks in early May, ending by late May or early June. Outmigration from the lower Trinity River, as indicated by monitoring near Willow Creek (RM 24), peaks in May and June, and continues through the fall. Coho salmon migrate up the Trinity River and Klamath River from mid-September through January and spawn from November through January. Emergence of coho salmon fry in the Trinity River begins as early as late February and continues through March. After their emergence from the gravel, fry use cobbles, or boulders for cover and typically defend a territory. Suitable territories may be extremely important for coho salmon juveniles, as Larkin found that the abundance of coho salmon may be limited by the availability of these appropriate habitats. In the summer, coho salmon parr reside in pools and near instream cover, such as large woody debris, overhanging vegetation, and undercut banks. Overwintering habitat is essential for coho salmon because juvenile coho salmon remain in the Trinity River Basin for their first winter and into the following spring. Preferred overwintering habitats are large mainstem, backwater, and secondary channel pools containing large woody debris, and undercut margins and debris near riffle margins. Instream residency occurs throughout the upper mainstem from Lewiston downstream to at least the confluence with the North Fork. Outmigration of 1-year-old coho salmon smolts begins in February and continues through May. Peak outmigrations occur in May in the Trinity River near Willow Creek. Outmigrant monitoring on the mainstern Trinity near Junction City and Willow Creek from 1992 to 1995 indicated that natural coho salmon smolt production is low and typically represents less than 3 percent of the total annual coho salmon smolt catch. Although the three species of anadromous salmonids that inhabit the Trinity River have unique habitat preferences and timing for their spawning, growth, and outmigrating life stages, these species share common life-history requirements that should be considered when making crucial decisions regarding restoration of the fisheries: 1. Spawning pairs require adequate space to construct and defend their redd, which commonly is associated with unique instream habitat features; 2. Spawning gravels with a low percentage of fine sediment facilitate adequate subgravel flow through the interstitial spaces in the redd, increasing successful egg hatch and sac fry survival. Excessive sand and silt loadings reduce the survival of eggs and sac fry, as well as fry emergence success; 3. Salmonid fry require low-velocity, shallow habitats — and, as they grow, a variety of habitat types are required that include faster, deeper water and instream cover; 4. Because of their extended residency in the Basin, coho salmon and steelhead must have abundant overwintering habitat composed of low-velocity pools and interstitial cobble spaces; and 5. Smolt survival is a function of fish size, water temperatures in the spring and early summer, and streamflow patterns. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) recognizes two ecotypes of steelhead based on sexual maturity at the time of river entry. Steelhead that enter the river in an immature state and mature several months later are termed “stream-maturing”; these are the summer-run steelhead. “Ocean-maturing” steelhead enter the river system while sexually mature and spawn shortly thereafter; ocean-maturing steelhead are referred to as “winter-run” steelhead. Portions of both groups may enter freshwater in spring or fall and are then called “spring-” or “fall-run” steelhead. Continued... In addition to runs of adult steelhead, the Klamath and Trinity Rivers also support a run of immature steelhead known as “half-pounders”, which spend only 2 to 4 months in the ocean before returning to the river in late summer and early fall. Half-pounders feed extensively in freshwater and are highly prized by sport anglers. Half-pounders overwinter in the river without spawning before returning to the ocean, and return as mature adults during subsequent migrations. Half-pounders have a very limited geographic distribution and are known to exist only in the Rogue, Klamath-Trinity, Mad, and Eel River systems. Steelhead enter the Klamath-Trinity Rivers throughout most of the year. Summer-run adults enter the stream between May 1 and October 30 and hold in the river for several months before spawning. Summer-run steelhead commonly reach Lewiston (RM 112.0) by early June and continue to arrive through July. They enter major tributary streams by August and remain in deep pools until they spawn in February. Winter-run steelhead enter the river between November 1 and April 30 and hold in relatively high-velocity habitats, such as riffles and runs; they spawn in April and May. Summer- and winter-run steelhead are, therefore, temporally and spatially isolated from each other. They do not interbreed because summer-run adults generally use areas that are farther upstream than areas used by winter-run adults. Spawning of all steelhead races in the Trinity River typically begins in February, peaks in March or April, and ends in early June. After emergence from spawning gravel, steelhead fry and juvenile steelhead use habitats similar to those of juvenile salmon, although rearing steelhead prefer higher velocities than do salmon of similar size. Everest and Sedell identified key winter habitat for steelhead as areas with boulder-rubble stream margins that are approximately 12 inches deep with low to near zero water velocities. Outmigration of steelhead smolts from the Trinity River above Junction City (RM 79.6) begins in early spring of their second or third year and peaks in late April and early May. Outmigration near Willow Creek (RM 24) begins in late March and early April, peaks in early May, and continues throughout June (USFWS, 1998). Although the primary focus of the Trinity River Flow Evaluation was on anadromous salmonids, the fish community in the Trinity River is composed of several additional species. Several native species are of biological, cultural, and economic significance, and their life histories and habitat requirements are briefly outlined here to illustrate the diversity of habitat required by the fish community. Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) are harvested by the Hoopa, Karuk, and Yurok Indians and remain an integral part of their culture today. Pacific lamprey are a parasitic species of anadromous lamprey native to the Trinity River. Adult Pacific lamprey migrate upstream and spawn during the spring. Eggs are deposited in pits excavated in gravel and cobble substrates, which are usually associated with run and riffle habitats similar in character to salmon spawning areas. The eggs hatch into a non-parasitic larval stage, referred to as an “ammocoete”. Ammocoetes drift downstream into slow-water habitats, where they burrow into sand or silt substrates. They spend from 4 to 5 years in freshwater, where they feed on organic detritus. The juveniles metamorphose into the adult form just prior to seaward migration, at which time they become parasitic. Adults remain in the ocean usually 6 to 18 months before they begin their spawning migration. Green Sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) are harvested by the Tribal fisheries in the lower Klamath and Trinity Rivers and these fish have cultural significance to the Hoopa, Karuk, and Yurok Indians. From 1982 through 1992, the harvest of green sturgeon on the Yurok Indian Reservation was fairly consistent, averaging just under 300 fish. Green sturgeon migrate up the Klamath and Trinity Rivers between late February and July to spawn. Gray’s Falls (RM 43) is believed to be the upstream limit of sturgeon migration in the Trinity River. Sturgeon spawn from March through July, peaking mid-April to mid-June. Juvenile green sturgeon are found in the Trinity River near Willow Creek from June through September, and appear to outmigrate during their first summer to the lower river or estuary, where they rear for some time before moving to the ocean. RESOURCES FOR THE TRINITY RIVERHatching to fry in shallow, low velocity waters

Juvenile “parrs” remain in freshwater streams

Smolting prepars juvenile salmonids for outmigration to the ocean

Life cycle timing

SUMMARY OF HABITAT REQUIREMENTS

FACTORS UNIQUE TO STEELHEAD

OTHER FISH SPECIES IN THE TRINITY RIVER