While there are dozens of milkweed species and subspecies in North America, within the Trinity River Watershed there are four documented species, including showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) narrowleaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis), heart leaf milkweed (Asclepias cordifolia) (DeCamp, 2021, p. 294, 362) and the rare lesser seen serpentine milkweed (Asclepias solanoana) (Kauffman, 2022, p. 155). Each type has unique leaf sets and structure topped with wonderful showy flowers and dramatically large seed pods that propagate via wind in the fall. The flowers are a haven for area pollinators and the plant itself plays a critical role in the majestic monarch butterfly migration. In our region, monarch butterflies, generally choose one type of milkweed, showy milkweed (A. speciosa), to lay their eggs and because of this, the availability and frequency of the plant along the monarch’s migratory path are critical to it’s survival (Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper, 2024).

Photo: Heart leaf milkweed (A. cordifolia) has matured it’s showy seed pods in the Trinity Alps. [Kiana Abel, TRRP]

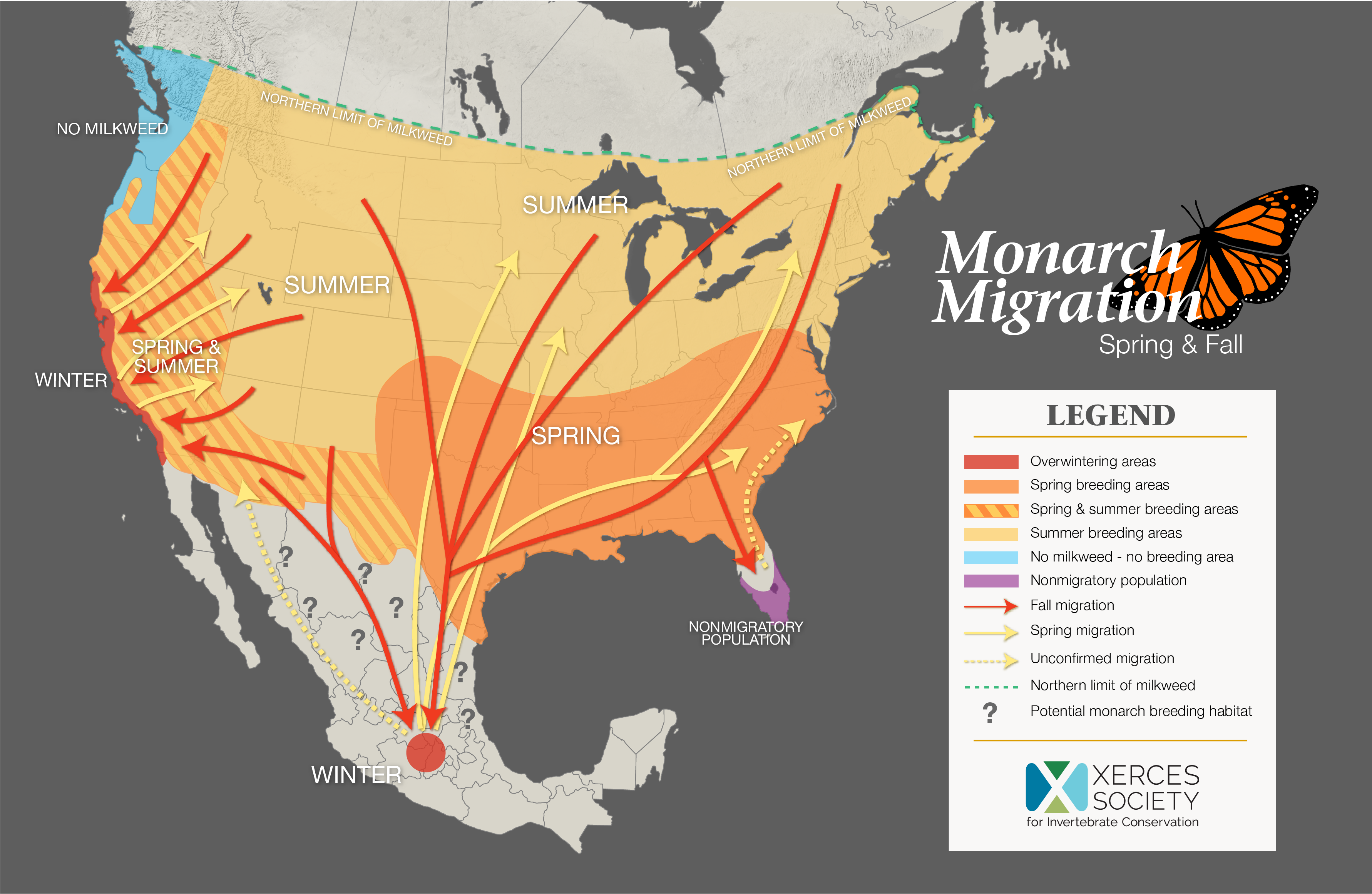

A monarch’s annual lifecycle goes through upwards of 4 generations during migration. Migration north (and east for western monarchs) happens typically between March and August each year. During migration, an adult female will lay eggs on the underside of young healthy milkweed leaves, hatch, eat, crystallize and repeat. As summer progresses, roughly in the third or fourth generation the western monarch will eventually turn south and west to return to their overwintering sites on the California coast (and in some cases Mexico).

All species of milkweeds are characteristic of the milky sap in their stems and leaves which contain a lethal brew of cardenolides (heart poison). If grazed, animals and insects are served a warning with distasteful, hairy leaves. If ingested, a grazer is confronted with vomiting and potentially death in higher doses. The negative effect on agricultural livestock like sheep and cows led farmers and agriculturalists toward eradication efforts. Over time, the combination of increased land use and herbicide led to a significant decline in available milkweed, with monarch populations following suit.

The handful of insects that do eat the plant are all incredibly colorful which in-turn serves as a warning to their predator’s (Monarch Joint Venture, 2024). If a monarch caterpillar were to be eaten it’s predator will encounter a nasty taste and hopefully drop it’s prey. For the majority of insects like bees, moths and other butterflies the main attraction to milkweed is the flower which provides nectar during a time in the summer when most other flowers have spent. For each type of milkweed found, the flowers are showy, intricate and are certainly worth a close-up look.

Milkweed has proved useful to people as well. Ethnobotanists have documented historic and current use of the plant in fiber, food and medicine in the United States and Canada. Milkweeds supply tough fibers for making cords, ropes as well as for course cloth. Native Californian tribes use the plant for all the purposes listed above. In one documented case of a Sierra Miwok woven deer net, the trap measured 40 feet in length and contains some 7,000 feet of cordage, which would have required the harvest of 35,000 plant stalks. Among Californian Native tribes, the most common documentation of use was to obtain a kind of chewing gum from the sap of showy milkweed (A. speciosa). The sticky white sap is heated slightly until it becomes solid, then added to salmon or deer gristle (Stevens, M., 2006).

The decline of wild milkweed plants as well as the majestic monarch butterfly has spawned a cultivation movement to encourage everyday gardeners to plant. If you reader, would like to cultivate milkweed in your pollinator garden, make sure to plant it in a location where it can expand. In suitable conditions, milkweed can outcompete other plants and on occasion infrastructure such as plant boxes or walkways. A second consideration is where the location of where you’d like to plant in accordance with the migratory path of the monarch. If you are in a costal overwintering area, it is more beneficial to monarchs to plant nectar plants versus nursery plants. A planting of A. speciosa may falsely signal that they are in a location fit for reproduction leading to a disruption in their migration cycle.

When you’ve picked the best species for your area you can propagate milkweed from seed or rhizome. Collect seeds from pods once they have ripened, but prior to splitting open. Experienced cultivators planting in high elevation or colder climates have documented higher success rates with seed by using a cold treatment for three months and then planting directly into the ground the first fall after collection (Stevens, M., 2006). Propagation by rhizome is also easy and reliable. Create cuttings when the plant is dormant and make sure the rhizome has at least one forming root bud. Success is also dependent on on timing. Harvest or divide plants at the beginning of the rainy season and plant them in the ground by late fall so they can develop enough root growth to survive the winter. Irrigation in the first year will improve survival, and by the second year the root system should be well enough established so plants will survive on their own (Stevens, M., 2006).

Citations

- DeCamp, K., Kierstead. J., Knorr, J. (2021) Wildflowers of California’s Klamath Mountains (Michael Kaufmann) (Second Edition). Backcountry Press.

- Kauffmann, M., Garwood, J. (2022) The Klamath Mountains: A natural history. (First Edition). Backcountry Press.

- Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper (2024) Western Monarch Biology: The monarch Life Cycle

- Monarch Joint Venture (2024) Monarch Annual Lifecycle

- Stevens, M. (2006) NRCS Plant Guide: Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service.

- How to Grow and Care for Common Milkweed (thespruce.com)

References

Ciesla, B. (2015) Milkweeds: Fascinating Plants, Home to Colorful Insects Colorado State University Extension Master Gardener in Larimer County.

Stevens, M. (2006) NRCS Plant Guide: Showy Milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Asclepias sp. Milkweed Native American Ethnobotany Data Base. A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants.

US Forest Service: Monarch Butterfly Biology United States Department of Agriculture US Forest Service

Serpentine milkweed (Asclepias solanoana) Calscape California Native Plant Society