Equisetum is a group of plants categorized as a fern that are often found in wet places. It superficially blends into the “grass-like” background of a wetland around rivers or marshes. This group is otherwise often called horsetails with 15 species found worldwide. There are four species most commonly found in the Klamath Mountains including Equisetum arvense (common or field horsetail) which happens to be the most common horsetail in the world.

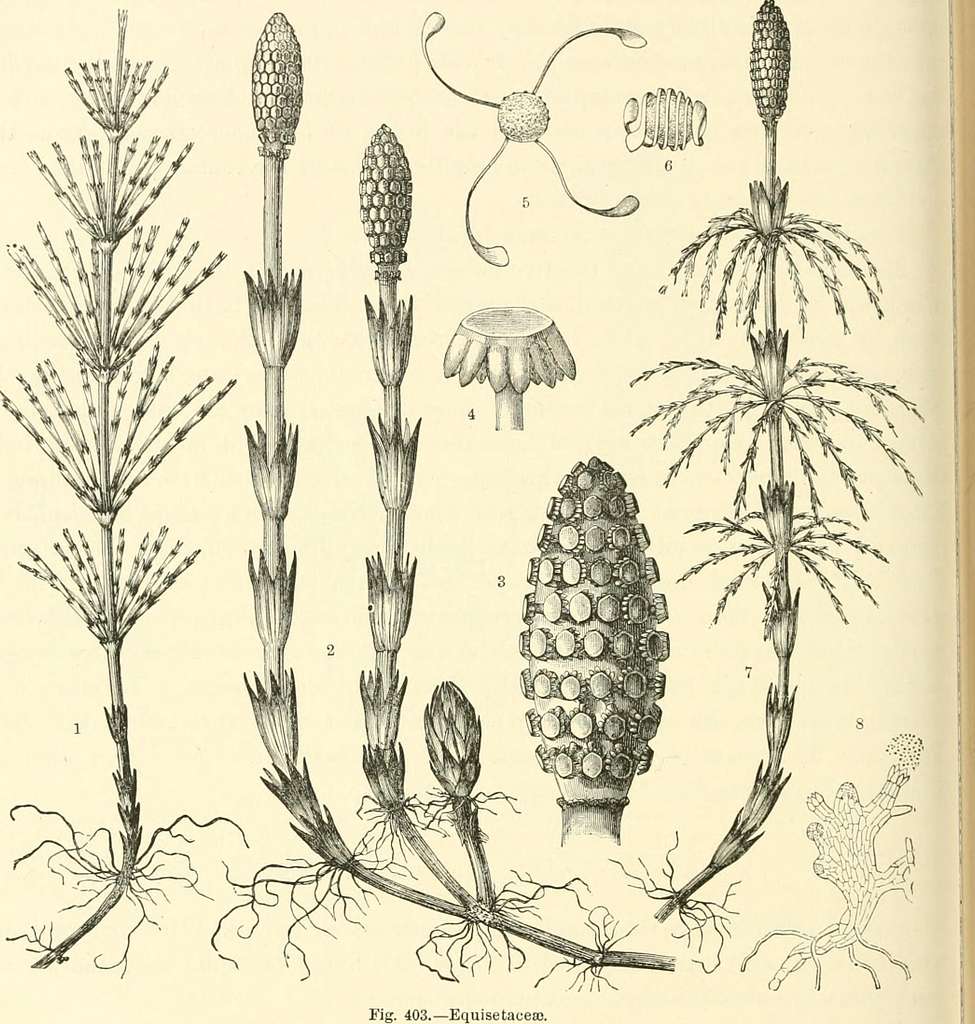

In 1883 a prominent plant taxonomist, August W. Eichler, divided the plant kingdom into two groups: Phanerogamae which reproduce by seed (via flower or cone) and Cryptogramae which reproduce via spore. The Klamath Mountains have an incredibly diverse existence of terrestrial cryptograms, which are represented by mosses, liverworts, lichens, ferns, forest mushrooms and algae [1]. As you may have deduced from the list, moisture plays a key roll for reproduction of a cryptogram. Classified within the fern family, the horsetail arrived on earth approximately 375 million years ago. The modern genus, Equisetum is a “living fossil” of the subclass Equisetaceae, which for 100 million years dominated the understory of Paleozoic forests [2]. The ancient genus ranged from large trees to the low lying species we commonly see today.

Functionally, Equisetum is rhizomatous – meaning it has more than one way of reproducing. Sideways roots spread the same plant horizontally in the ground in addition to the little spore-bearing “cones” (strobili) which allow it a mechanism for sexual reproduction.

Most commonly you’ll see the plant spread, or propagate, along the river by being scoured out of the ground by high flows and wadded up with leaves, wood, and sediment deposited along the river bar. This is a natural process for plants to establish along depositional areas (sediment accumulation areas) freshly created along the banks of a dynamic river.

Reproductive spores of E. arvense have four ribbon-like appendages sensible to moisture. These “legs” fold back around the main body in humid air and deploy upon drying. Check out a video of this process below!

The sections of the plant are jointed and clasping each-other with little “frills” which are the true leaves of the plant. Find these leaves at the many joints which make up the stem. These little joints can be popped apart and the inside is rough, hollow and crunchy. The interior of the stems are made up of strong, lengthwise ridges that have been documented as being useful to scour materials like arrows, as well as polish metals and musical instruments [2].

Photo: Equisetum found along the Trinity River. [Simone Groves, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries]

Although horsetails are known to be toxic to horses and other livestock, there are also documented traditional medicinal use from around the world ranging from treatments of skin disorders to lung diseases [2]. Within North American traditional uses, E. arvense is documented with an incredible range listing; food, drug, instrument, scouring material, fiber, soap and dye [3]!

- Garwood, J., Kauffmann, M. The Klamath Mountains A Natural History. Backcountry Press. First Edition. 2022. Pg. 167.

- Equisetum. Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia [Equisetum – Wikipedia]

- Native American Ethnobotany Database. Equisetum arvense L., [http://naeb.brit.org/uses/species/1421/]

Simone Groves, Riparian Ecologist, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries

Simone is first generation California transplant of scottish descent raised in the unceded territories of the Raymatush in the rural west peninsula of the SF Bay where farmers, farm workers and hippies form the heart of the small town. She graduated in 2016 from Humboldt State University with a BS in Botany and has worked in the outskirts of rural Humboldt county on Natural Resource and Land management since 2013. She is passionate about plants and their interactions with dynamic systems as a mechanism for relearning our human-landscape interdependence.