As the weather starts to warm, California’s hillsides turn golden as grasses dry and take on a reflective sheen. Not only does California’s nickname “the Golden State” refer to it’s historic connection to the gold rush, it also refers to the rolling golden hills of native flowers, like the California golden poppy and less distinct but no less important the native grasses of California. California’s grasslands are a subtle and complex community of individuals which each invite the passerby to slow down and look carefully. One can also trace the last vestiges of water and see where the moisture lingers on the landscape. These last little patches of green show photosynthetic organisms reluctant to take shelter from the summer heat.

Historically it was farmers who were in touch with the detailed eye and mind tuned to the life cycle of grasses. To be a farmer who makes hay, is to understand the boom-and-bust lifecycle of being a grass. As many ranchers will say – being a rancher is really learning to be a grass-farmer. It is an intimate relationship to learn the rhythm of grass growing, to slow down and tap into the cycle. There is a critical threshold in the season, where all the grasses race at a break-neck pace to produce seed. As part of a grass’s strategy, it tracks day-by-day weather in a race to produce and distribute seed in the heat of summer. As a hay producer, it’s best to harvest your hay before all the energy has gone up into the seed and hardened off. This will allow some of the sugars to be readily available for consumption when an animal goes to eat it. If the grass is too far along towards producing its seed, the sugars in the grass become all locked up and stored into their long term, harder to digest form.

If you’ve ever been curious about grasses, Trinity County has some beautiful remnant examples of grasslands clinging on to the edges of areas where mining did not bury their seeds beneath the sorted rocks. When identifying grasses, I find that it can be easiest to start with the things that you’ll see a lot of and try to find “friends” in the population. Each person relates to plants differently, but I find that it can help to try to find a few native grasses and a few non-native grasses to learn to train your eye to their differences. Knowing a handful of native and a handful of non-native grasses is a great place to start.

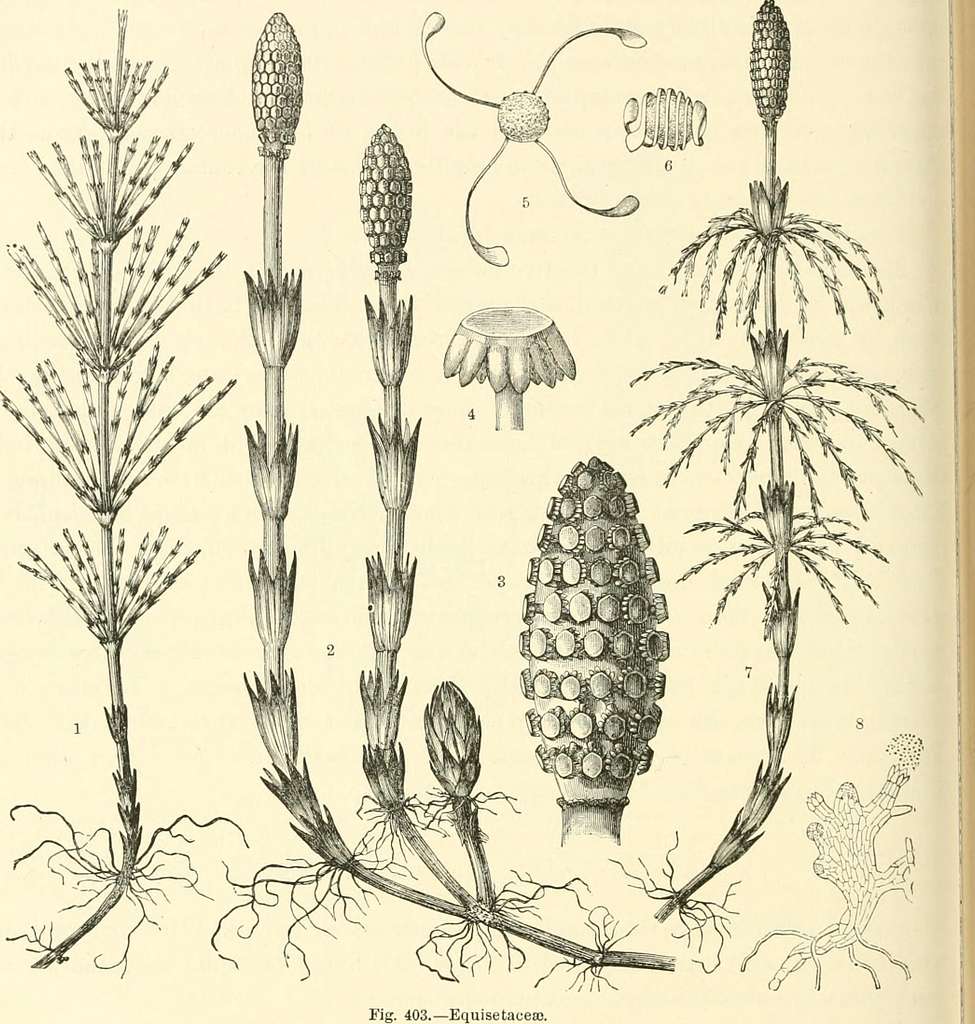

Comparing grass cousins

Here is Bromus diandrus or “rip gut brome” [iNaturalist John Lynden] so named for its ability to get the long awns of the plant (the bristle or hairy growth that helps carry a seed) all tangled and poking into the skin, mouth or gut of herbivores munching in grasslands. Rip gut brome was introduced to California from European Mediterranean areas and is considered invasive and harmful to crops and foragers alike.

Because grasses are difficult to discern, I’ve noted to visit and reexamine them as the season progresses. With each stage of development from flower to seed each species can change significantly showing their true colors. As Bromus diandrus develops it changes colors and can look quite purple.

Here’s a common native grass that looks quite similar to Bromus diandrus. A cousin to B. diandrus, this is Bromus carinatus or California brome [Rob Irwin via iNaturalist] which is a native bunch grass that can be found in many types of habitat.

California brome pollinates via wind, is a great asset in erosion control and is well adapted to survive under a regime of frequent fire. It is also an important food for bear, elk, black tailed deer and seed eating bird species of California.

Look closely when comparing these two brome species by looking at the hair-like awns sticking out of the flower.

Non-Native Grasses

As livestock were introduced to California, farmers often seeded grasses as forage so their animals would be well-fed where they landed. The easy and short list of these species is a great starting place to begin to recognize grasses. These species include orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata), rye grass (lolium perenne), wild oats (Avena sp). Avena or wild oats are the same oats that we eat for oatmeal or give to our horses for grain.

Native Grasses

And now for some of the native species of grasses! There are three classics to get to know in our area which are blue wild rye (Elymus glaucus), California oatgrass (Danthonia californica) and purple needle grass.

Blue wild rye (Elymus glaucus)

This grass is a tall hearty looking grass with a large seed. It’s very hard to photograph the whole seed head because it is so long and tall, but once you get to know this plant it’s quite distinct. Blue wildrye provides excellent habitat for birds, mammals and waterfowl, can be used to stabilize streambanks, and is very tolerant to fire. Early in the season it provides forage and the seed is an excellent summertime food source for native mammals and birds [USDA Blue Wildrye (Elymus glaucus) Plant Guide].

California Oatgrass (Danthonia californica)

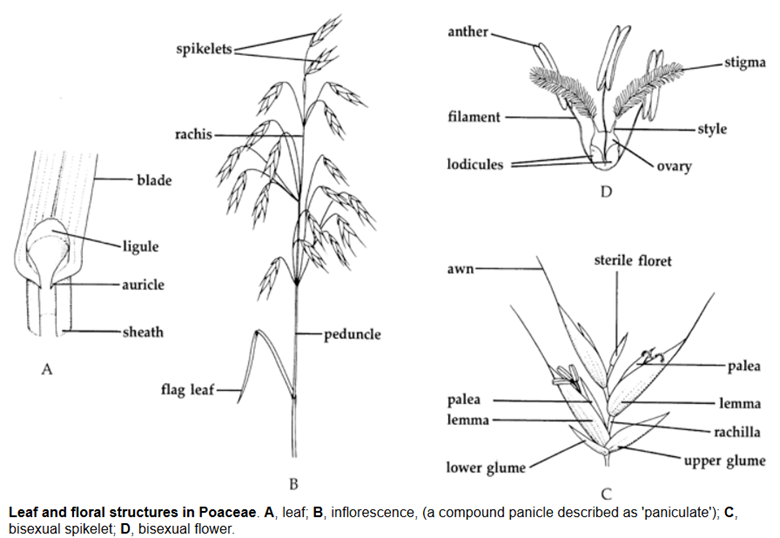

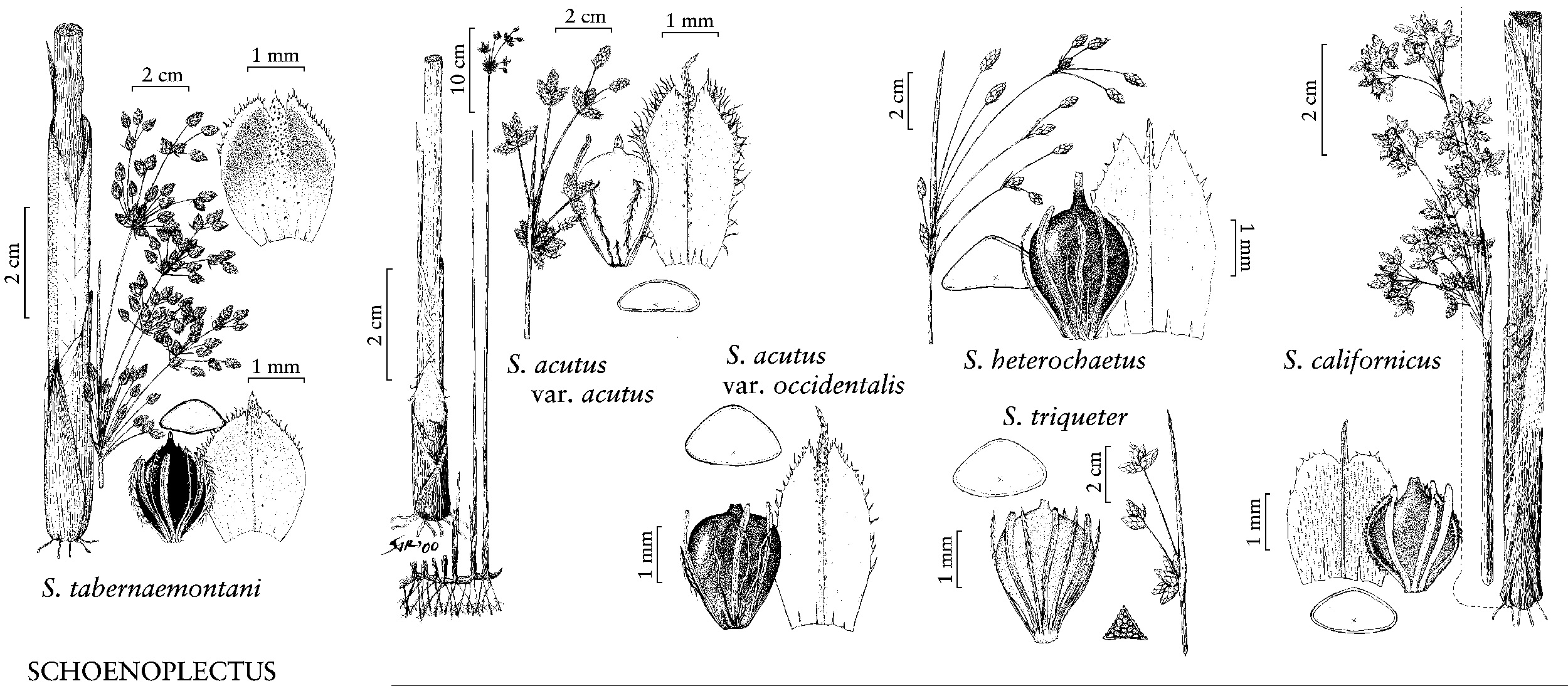

Danthonia as the genus that represents a variety of native oats, and when you tune your eye you’ll notice slight variation within the group along with some similarities. Their inflorescence (arrangement of the flowers on a plant) is composed of 3-5 spikelets and it is a pretty distinct recipe once you start to recognize it. They have relatively short peduncles (stalks that hold the flower or seed), only about 1-2 feet above the ground and their most distinctive feature are their “hairy arm pits.” Danthonia tends to have very hairy leaves and sometimes particularly long hairs right where the leaf separates from the stalk. Danthonia also looks to me like a little field of tiny stars, as they stand in such a distinct pattern along the ground.

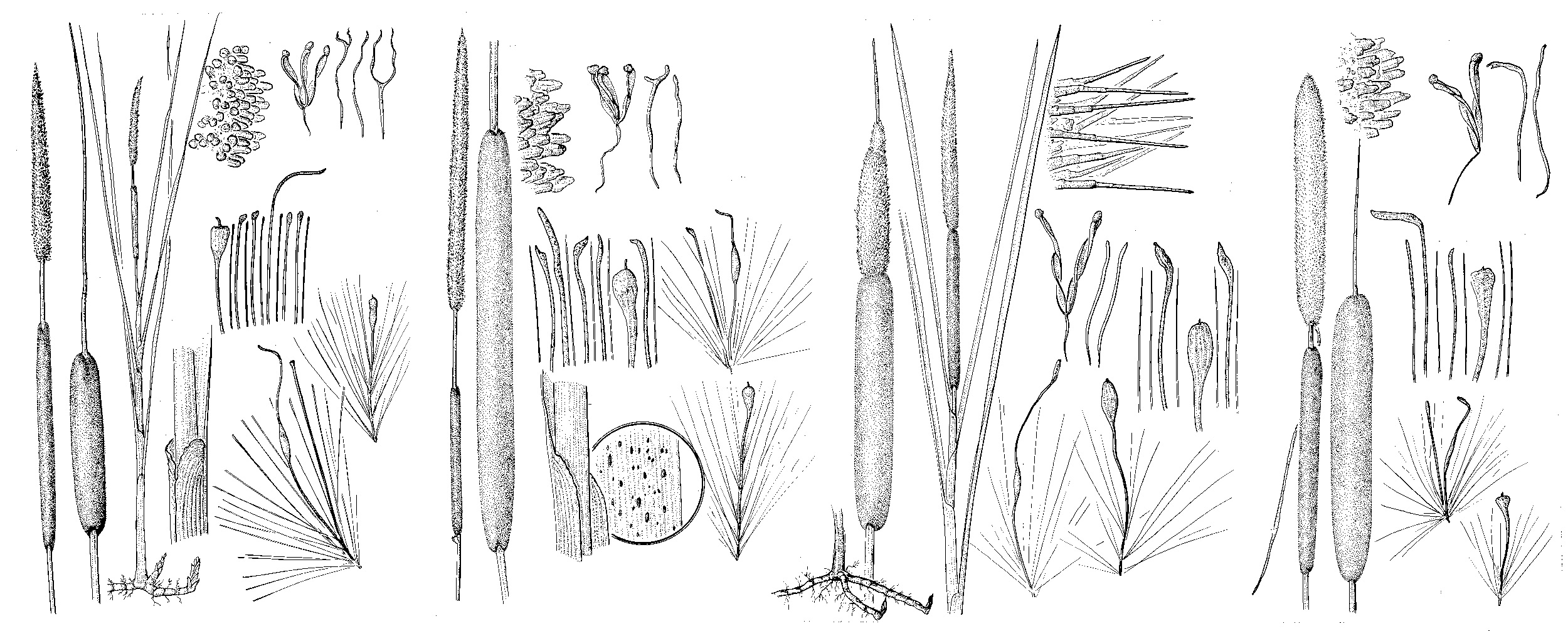

Purple Needlegrass (Stipa pulchra) (Nassella pulchra)

Lastly, Stipa pulchra, recently renamed to Nassella pulchra and commonly known as purple needlegrass is a grass that I – personally as a plant person – have heard a lot about throughout the state. Purple needle grass is the most widespread native grass in California and was named the “state grass” in 2004. In my experience I’ve have never seen it doing quite as well as the populations you can find here in Trinity County. This plant has long awns similar to rip gut brome but is soft to the touch while brome is typically quite coarse and harsh.

Purple needlegrass is drought tolerant and produces a lot of seed which helps to suppress non-native grass species. This grass supports native oak habitats and provides nursery habitat for caterpillars and butterflies of California.

Getting to know grasses is a process of revisiting them frequently to see the way that they change through the year. Touching and observing their basal leaves versus their flowering stalks can help you get to know the ways that they are similar and different from each other. To me, the jovial angle that each grass holds its seed is an expression of its personality and projects attitude. As the seeds mature, usually the stems of the grass start to grow heavy, and once the seeds are dispersed, they’ll spring back up again.

Grasses are a huge part of the plants that we see in our daily lives. Their role creating tiny holes for insects to live in and deep roots which hold our soils together are foundational to a healthy landscape. It’s easy to overlook the niche of grasses when we all spend much of our time trying to weed whack them down. I encourage you to try to take that extra moment to see if you can identify if a grass is native or non-native, bunchgrass or annual grass. These little details are small pieces of history that we used to know in times long past.

References

- Bromus carinatus

- Native American Ethnobotanical Database: Brome

- https://ucanr.edu/sites/default/files/2016-03/235849.pdf

- Blue Wildrye (Elymus glaucus) Plant Guide

- Nassella pulchra – Wikipedia

- iNaturalist see individual links for details for each species

Simone Groves, Riparian Ecologist, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries

Simone is first generation California transplant of Scottish descent raised in the unceded territories of the Raymatush in the rural west peninsula of the SF Bay where farmers, farm workers and hippies form the heart of the small town. She graduated in 2016 from Humboldt State University with a BS in Botany and has worked in the outskirts of rural Humboldt county on Natural Resource and Land management since 2013. She is passionate about plants and their interactions with dynamic systems as a mechanism for relearning our human-landscape interdependence.