Water Year 25 thus far has been a good year for Trinity Reservoir. In October, Trinity Reservoir measured in at 70% full with 1.7 million acre feet. Seasonal storms have recently pushed storage over 2 million acre feet (or 84%). In December, flows were held steady at 1500 cfs through January and increased to 3500 cfs after several atmospheric river systems passed through in early February.

Feb. Forecast – California-Nevada River Forecast Center

The volume of environmental flow releases for the Trinity River Restoration Program’s Wet-Season Baseflow Period (Feb. 15-Apr. 14) are determined by a conservative monthly inflow projection for Trinity Reservoir from the California Department of Water Resources (90% B120) in February, March with the final determination in April.

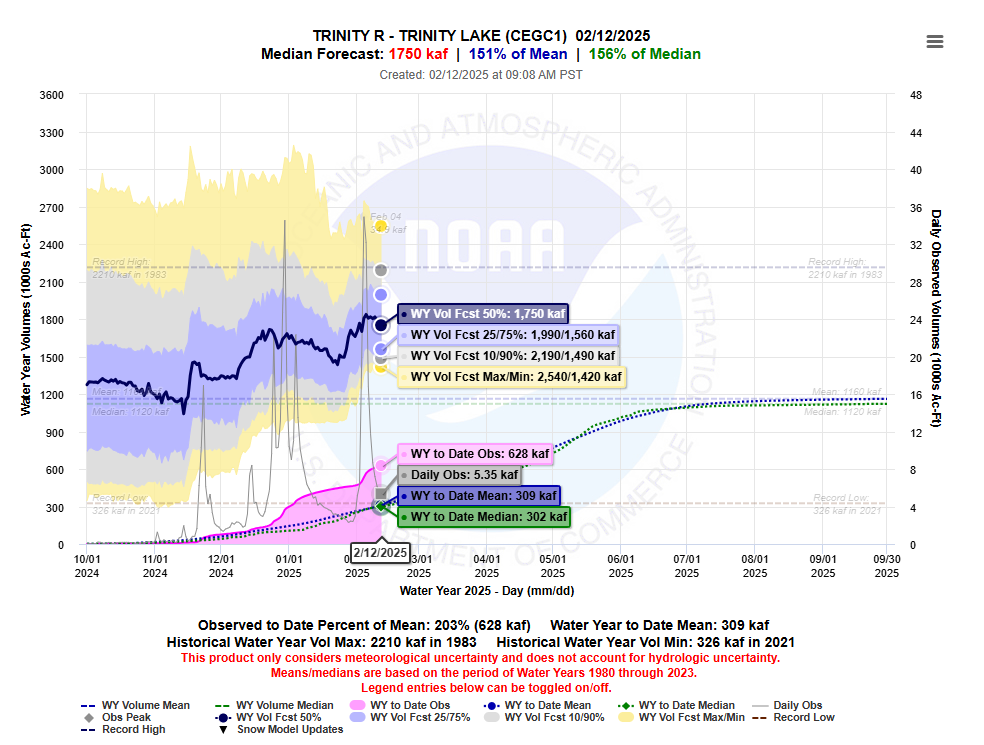

Prior to the official determination, which is published around the 10th of the month, water managers follow the California-Nevada River Forecast Center Median forecast for Trinity Lake inflow to stay abreast of the water year projections thus far.

The graph (shown in screen shot above) can be a little daunting to read, but when armed with the appropriate information is discernable for any viewer.

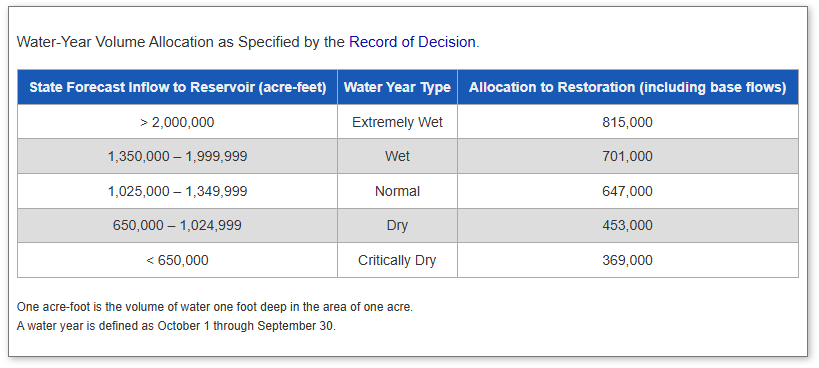

The Program’s Water-Year Volume Allocation as specified by the Record of Decision is outlined in the table below. The far left column is the threshold amount of state forecasted inflow in the Trinity Reservoir listed in acre feet which determines the center column, water year type. Then in the right column is listed the allocation to restoration for that water year, which includes baseflows.

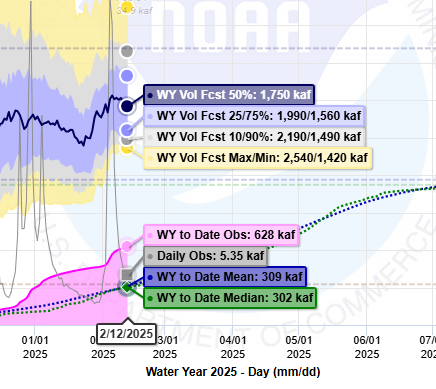

Return now to an enlargement of the CNRFC forecast screenshot from Feb 12. Check out the light grey box “WY Vol Fcst 10/90%: 2,190/1,490 kaf” which reads longform as the following;

As of Feb. 12, the 10% of probability for Trinity Lake Inflow is predicted as 2,190,000 acre feet and the 90% of probability is 1,490,000 acre feet. Translated there is a 10% probability that the Trinity Allocation is predicted as “Wet” and a 90% probability is also “Wet”.

As managers track the predicted inflow via CNRFC, the Program’s Flow Workgroup develops hydrograph scenarios to use when the final determination is published by the California Department of Water Resources. The two agencies use different methods when it comes to these prediction tools, the California Department of Water Resources uses data that has a weighted average to compute statewide Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) and is known as a more conservative forecast method when comparing the two.

Wet-Season Baseflow Period (Feb. 15 – Apr. 14)

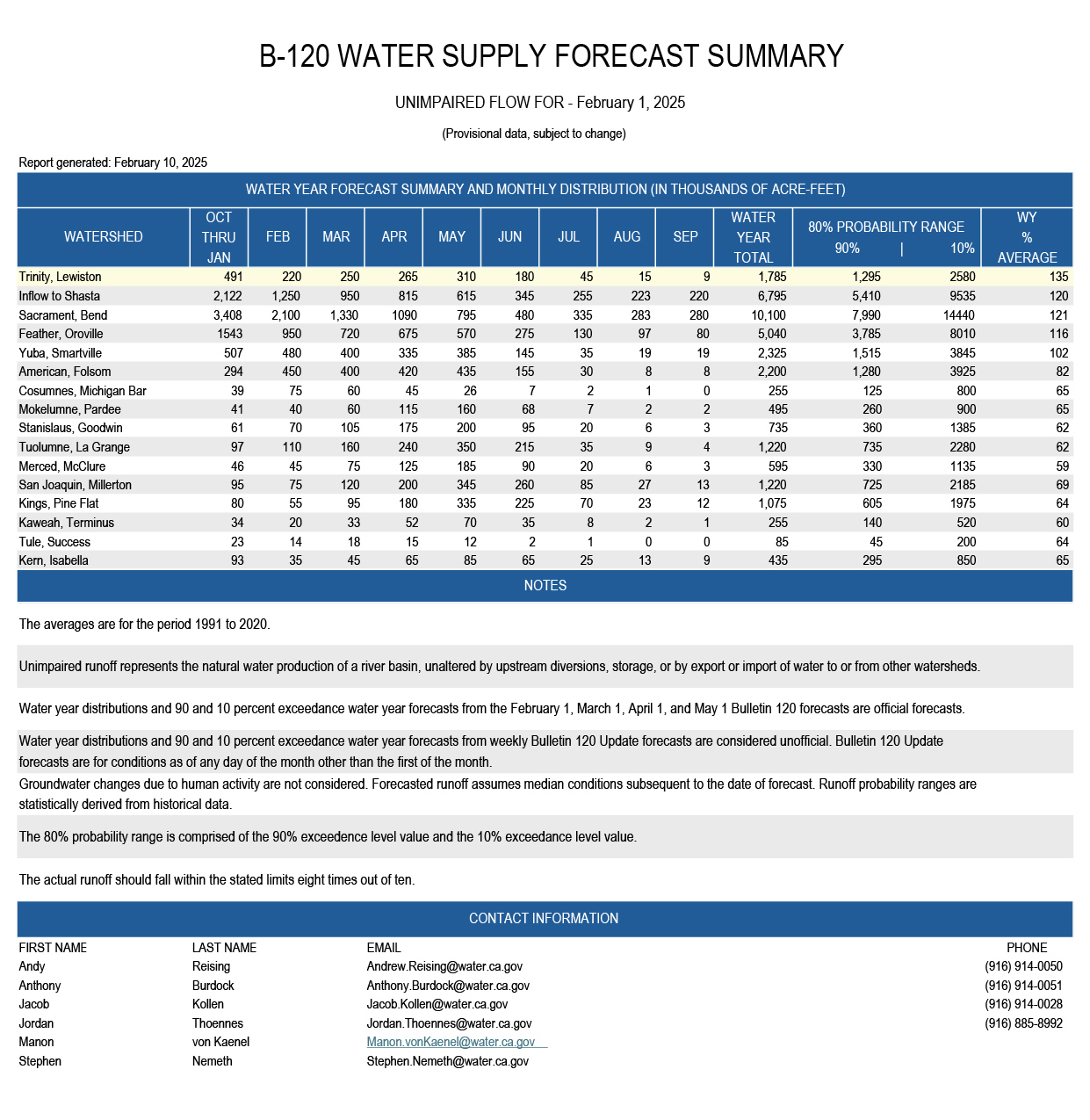

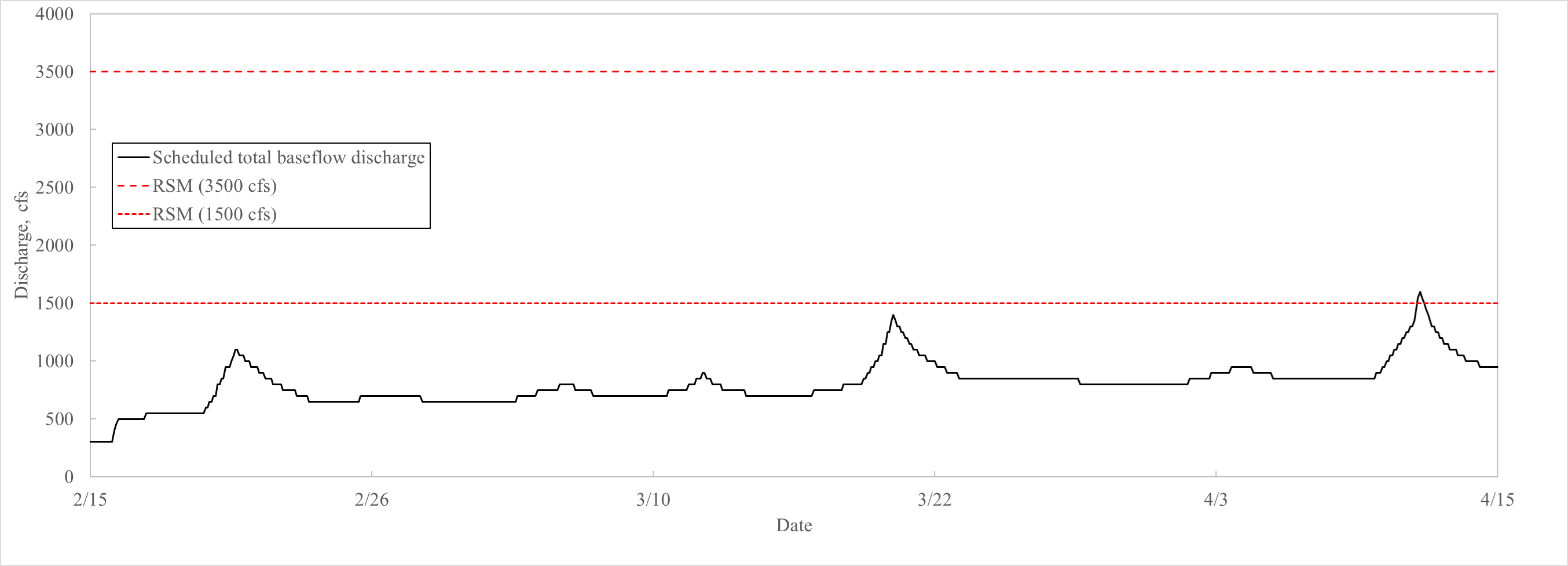

The next period within the Trinity River Restoration Program environmental flow management is the Wet-Season Baseflow Period, which initiates Feb. 15. The California Department of Water Resources February 90% B120 declaration was published on Feb. 11 as “normal” with the 90% determination at 1,295,000 acre feet.

The hydrograph developed by the Program with the “normal” water allocation does not exceed the current Trinity Reservoir dam releases which have ranged from 1500 cfs to 3500 cfs and are anticipated for the remainder of February because the reservoir is significantly encroached per the safety of dam criteria. For water accounting, the Program will deduct 60,000 acre feet from Reclamation flows during this period (Feb. 15 – Mar. 14), thus saving the reservoir valuable storage in the summer months.

With the river at levels above 300 cfs there are benefits to Trinity River salmonids as wetted areas are providing additional areas to biology within the system. Any reduction in flows would inhibit or halt such production in areas wetted by current flows.

Of course, unexpected flows always come as a shock. This water year has been unique in that maintenance on Clear Creek tunnel has initiated the need to send storage management releases down the Trinity versus to Whiskeytown Reservoir. To remain prepared, river enthusiasts should expect changing flows authorized by Reclamation through the month of March.

Prior to the next period (Apr. 15 – variable), the Program has a check-in on Mar. 15 to adjust flows to the March 90% B120 declaration. In April, the Program implements it’s spring snow-melt and recession hydrograph following the final B120 water year determination by the Department of Water Resources.