Freshwater Mussels in the Trinity River

Freshwater mussels are considered to be one of the most sensitive and threatened aquatic species within Northwestern watersheds. In North America, there are 297 known freshwater mussel species. Nearly three-quarters of these are considered imperiled, and more than 35 species have gone extinct in the last century. Eight species are known to exist west of the Continental Divide. Mussels have a fascinating life history strategy, which involves parasitizing on fish during their larval stage, and can live to be over 100 years old. They are considered an indicator species, like the good ole canary in a coal mine, as they require pristine water quality to thrive.

Life History, Strategy and Anatomy

To the unknowing eye, freshwater mussels look very similar to saltwater mussels as they are both bivalves, meaning they have 2 shells connected with a hinge. They are also both filter feeders and both belong to the class Bivalvia in the phylum Mollusca. Despite being named and shaped similarly, saltwater mussels, are however more closely related to oysters and scallops than they are to freshwater mussels, and thus have developed different evolutionary strategies. Saltwater mussels use a byssus thread to attach themselves to underwater structures, while freshwater mussels use a foot to move short distances and bury themselves. There are also differences in their sexual reproduction strategies. Saltwater mussels reproduce by ejecting the sperm and the eggs into the water column, where they fertilize and develop. With freshwater mussels, on the other hand, the sperm is ejected into the water column and inhaled by a female mussel downstream. The egg is then fertilized within a special part of the female mussel’s gills, and she exhales the baby mussels (called glochidia) after they are developed.

All freshwater mussels have:

- a hinge, which connects the two shells

- a raised, rounded area along the dorsal edge called, a beak

- a foot used for motion and feeding

- a thin sheet of tissue that envelopes the body within the shell, called a mantle

- and inhalant/exhalant features along said mantle

Some mussels have pseudocardinal teeth, which are short, stout structures below the beak. There are many more features with very technical names, but these are the most useful anatomical structures for identification in our region.

Western pearlshell mussel (Margaritifera falcata)

In the Trinity River, there is one confirmed species of freshwater mussel – the Western pearlshell mussel (Margaritifera falcata), which have very prominent pseudocardinal teeth. The Klamath River has also documented populations of the Western ridged mussel (Gonidia angulata), which have an obvious ridge on the outside of the shell, and floaters (Anodonta spp.) which are small and have neither teeth nor ridges.

Check out this article from the Mid-Klamath Watershed Council to learn more about Klamath’s freshwater mussels.

Photo Credit: Klamath River mussel bed above Rock Creek on 7-5-18. Mid-Klamath Watershed Council.

Western pearlshell mussels are known as being the longest-lived and slowest-growing mussel species in North America. In fact, they are the oldest freshwater invertebrates in the world. Their age can be estimated by counting the growth rings on their shells, similar to the growth rings on trees. The black, concentric rings are thought to represent winter rest periods. Some Western pearlshells have been documented to live over 100 years, meaning that some of these mollusks may have been in our river since it was buzzing with dredgers and mining activity in the early 1900s.

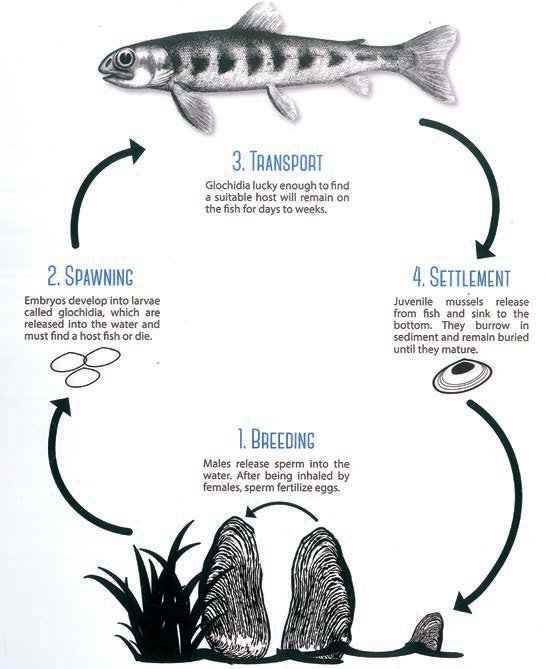

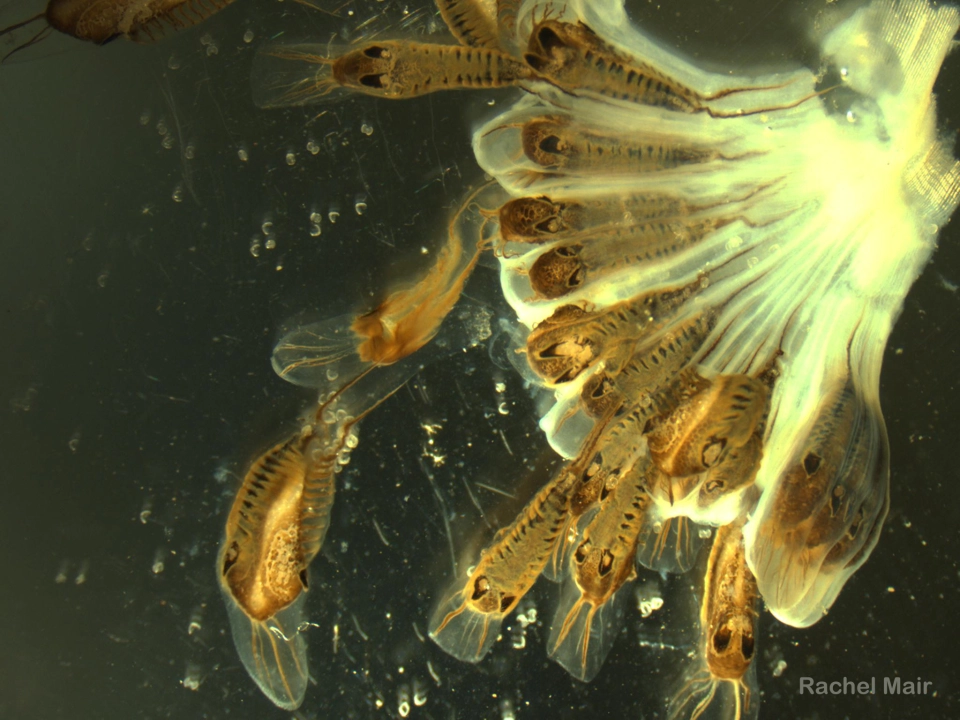

The foot on freshwater mussels aids in movement, but mussels are still very limited in their ability to transport throughout a stream. In order to colonize different parts of a river system, particularly upstream, after being released by the female as described below, the larvae (called glochidia) attach to fish passing by becoming parasitic. In the case of the Western pearlshell, the glochidia are released into the water where they clamp onto the gills of salmonids (particularly chinook salmon and steelhead) to hitch a ride upstream. After a short period (typically between a week and a month), the glochidia drop off into existing mussel beds (see the diagram borrowed from the Mid-Klamath Watershed Council).

Similar to salmonid migration, in which the salmon return to their natal stream, mussels can identify ideal locations to drop from their host and landing in existing beds of freshwater mussels. This life stage is one of the most fascinating aspects of this species. Originally the larval stage mussels were thought to be an entirely different parasitic invertebrate species yet scientists recently realized they are actually freshwater mussels in an immature life phase. Other species of mussels may parasitize different parts of their host fish, with some sending worm-like tendrils into the fish’s gills to sap vital resources. However, it is not thought that the mussels have a significant impact on the health of their host fish.

Pearlshell species can release their glochidia in aggregates, called conglutinates, which are bound by mucus. They seem to reproduce in spring and summer, though few studies have been conducted on the life cycle of our Western pearlshells. Though there is no scientifically defined relationship between water temperature and spawning (due to a lack of study), it has been observed in a study conducted in the state of Washington that mussels in warmer waters spawn earlier than those in cooler waters.

Ecological Benefits

Freshwater mussels have many benefits to stream ecology and have a major influence on the aquatic food web. They are filter feeders and they have separate orifices for inhaling and exhaling, which is how they derive nutrients. They filter tiny, suspended particles, including sediment, algae, bacteria and zooplankton out of the water column. Some of these particles are bound to larger particles within the mussels and expelled, where they sink to the bottom and feed benthic macroinvertebrates. Individuals in some species of freshwater mussels can filter up to 15 gallons of water per day, reducing turbidity and improving water quality. This cycling of nutrients also supports the growth of emergent plants, fostering a riparian habitat that benefits salmonids, which mussels are dependent upon. To be cliché, it’s all connected.

Freshwater mussels also help increase the exchange of nutrients, including oxygen, between sediments and the water column, in a similar mechanism to earthworms in the soil. They increase sediment porosity and allow the sediment to retain more organic matter. This ultimately improves the quality of aquatic habitat, allowing for a higher diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates.

Though not known for being a delicious treat to humans, mussels are an important food source for otters, raccoons and skunks. Healthy mussel populations are unaffected by natural predation, but low populations may be at risk of extirpation, and overly high populations may encourage excessive predator populations.

Trinity River Mussel Surveys and Conservation

In 2020, the Bureau of Land Management conducted a qualitative study of freshwater mussels on the Trinity River. A crew surveyed the upper 40 miles below Lewiston Dam and identified mussel beds as high, medium, and low density, and marked their locations on a map. This effort helps inform necessary conservation actions on project sites. If a mussel bed is known to be directly or indirectly affected from restoration activities, the Best Management Practice is to relocate a percentage of the population to an existing mussel bed upstream of their current location.

Relocation of freshwater mussels can be a tricky business. The species are incredibly sensitive to temperature and water quality conditions, so efforts must be conducted with efficiency and special care. It’s important to avoid moving mussels during certain times of the year when they are the most sensitive, which is when they are in their reproductive stages between December and July.

The long lived and sensitive nature of freshwater mussels is one reason it’s important to manage the Trinity River for long term impacts. Since mussels cannot move quickly to escape suboptimal conditions, their population fluctuations can reflect cumulative effects of environmental conditions, so studying and understanding freshwater mussels can be indicative of some aspects of riverine health. Despite being rather uncharismatic and tremendously understudied, the role that freshwater mussels play within aquatic ecosystems is invaluable.

Veronica Yates, Riparian Ecologist

(former) Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries Department, Weaverville