The Trinity River

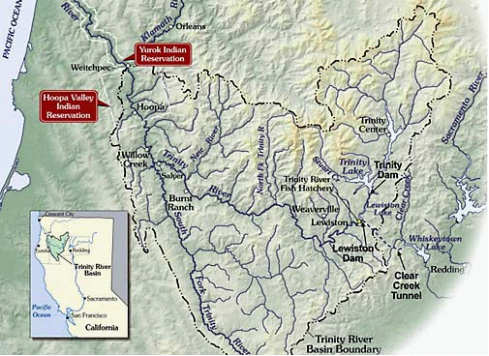

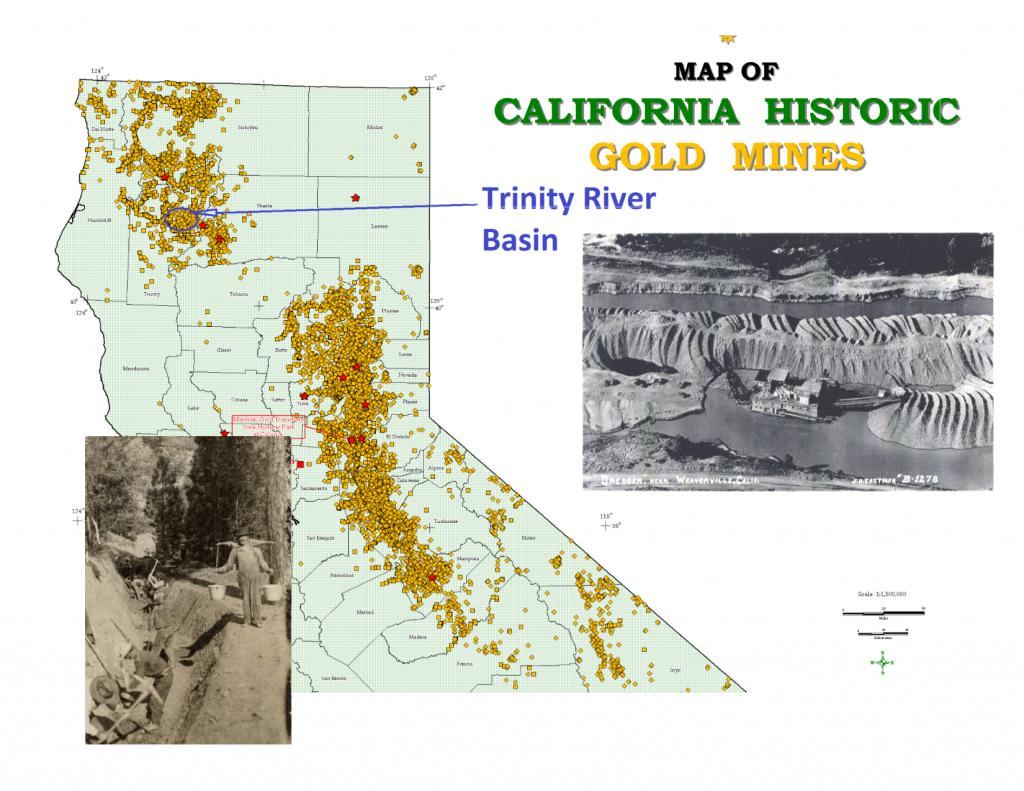

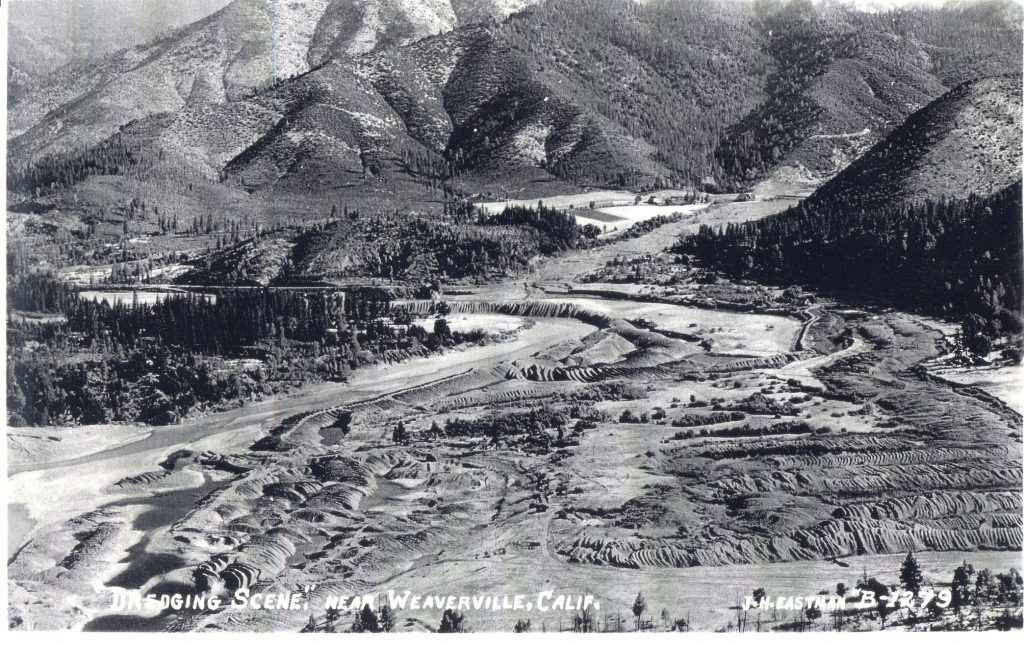

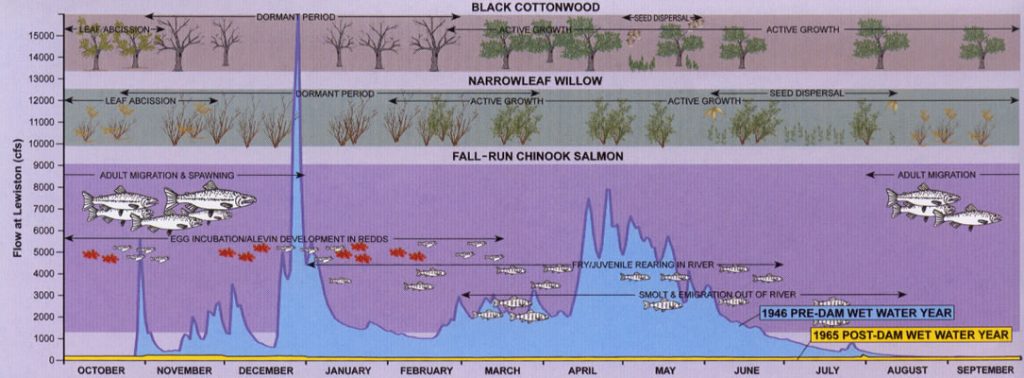

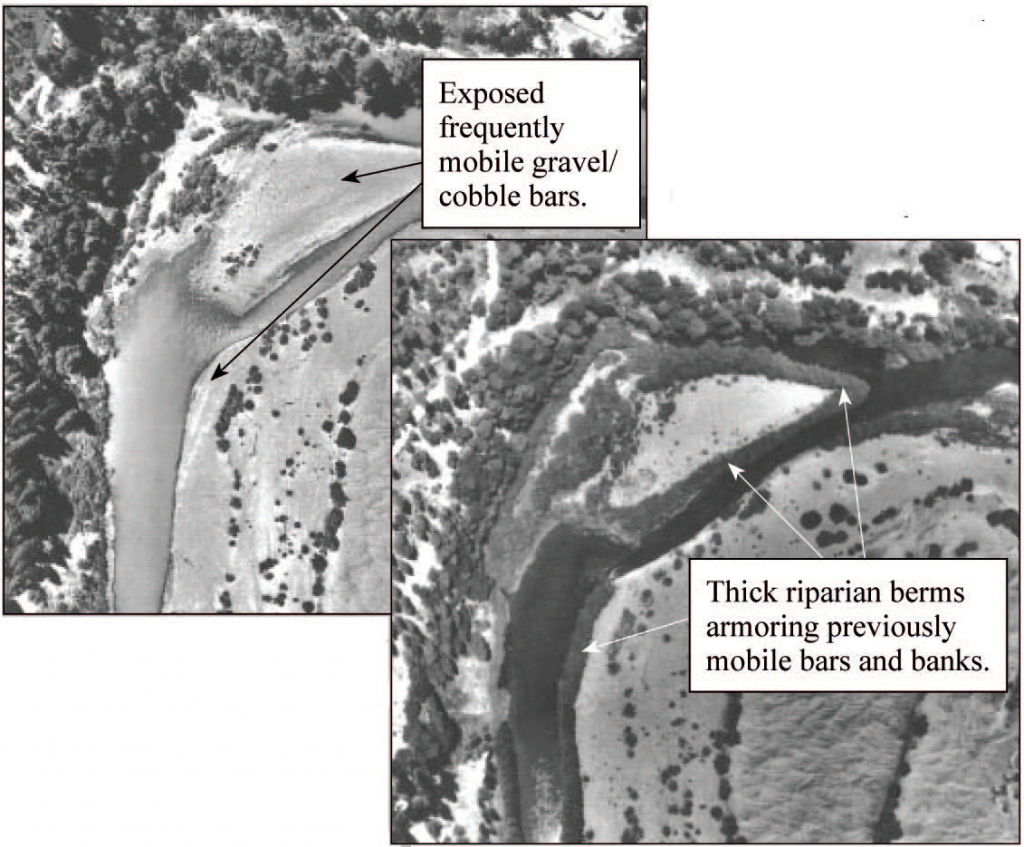

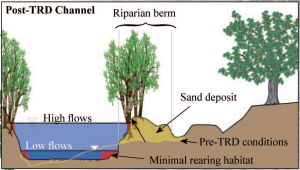

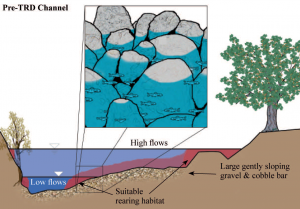

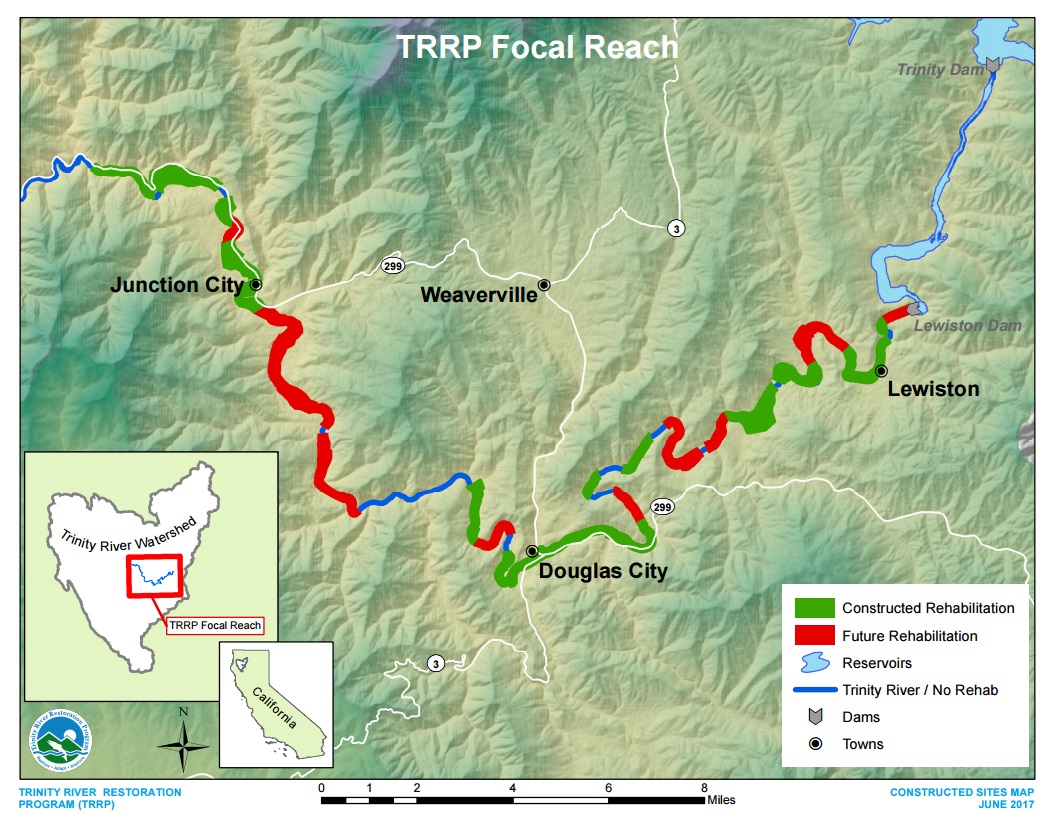

The Trinity River begins in the rugged Trinity Alps in northwestern California. The river tumbles through steep canyons and meanders through broad valleys until it joins with the Klamath River to flow into the Pacific Ocean. This powerful river once supported large populations of fall- and spring-run Chinook salmon, as well as smaller runs of coho salmon and steelhead. Floods, as predictable as the salmon, refreshed spawning gravels, scoured deep holes, and provided clear, cool water. Today, as for thousands of years, the Hoopa Valley Tribe and Yurok Tribe use the fish, plants, and animals in and along the Trinity River for subsistence, cultural, ceremonial, and commercial purposes. Water diversions from the dams combined with impacts from land use pushed the river past its regenerative capacity. By 1970, less than 10 years after the dams were completed, the extent of habitat alteration and decline in salmon and steelhead populations became obvious. Intent on reversing the decline, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hoopa Valley Tribe and other agencies began studies that culminated in the Trinity River Flow Evaluation Study. Completed in June 1999, this study is the foundation of the Trinity River Restoration Program which is designed to restore naturally-spawning populations of salmon and steelhead to near pre-dam levels. Historically healthy populations of steelhead (Oncorphynchus myskiss), coho salmon (O. kisutch), and Chinook salmon (O. tshawytscha) existed and thrived on the Trinity River. Commerical, Tribal, and sport fisheries continue to depend on these healthy fish populations from the river. Although the three species of anadromous salmonids that inhabit the Trinity River have unique habitat preferences and timing for their spawning, growth, and outmigrating life stages, these species share common life-history requirements that should be considered when making crucial decisions regarding restoration of the fisheries. The Trinity River Restoration Program considers these life histories and habitat requirements in planning, design, implementation, and monitoring activities: 1. Spawning pairs require adequate space to construct and defend their redd, which commonly is associated with unique instream habitat features; 2. Spawning gravels with a low percentage of fine sediment facilitate adequate subgravel flow through the interstitial spaces in the redd, increasing successful egg hatch and sac fry survival. Excessive sand and silt loadings reduce the survival of eggs and sac fry, as well as fry emergence success; 3. Salmonid fry require low-velocity, shallow habitats — and, as they grow, a variety of habitat types are required that include faster, deeper water and instrearn cover; 4. Because of their extended residency in the Basin, coho salmon and steelhead must have abundant overwintering habitat composed of low-velocity pools and interstitial cobble spaces; and 5. Smolt survival is a function of fish size, water temperatures in the spring and early summer, and streamflow patterns. TRRP Restoration Reach on the Trinity River below Lewiston Dam to the confluence of the North Fork Trinity River The fishery and other resources of the Trinity River and the lower Klamath River Basins defined the life and culture of area Indians since time immemorial. Salmon and other fish historically provided the primary dietary staple for the Indians in the area; prior to non-Indian settlement in the basin, reports indicate that local Indians consumed over two million pounds of salmon annually. The fishery resources supported commercial and subsistence economies for the Indians and also played a significant role in their religious beliefs. Fishery resources of the area have been characterized as “not much less necessary to the existence of the Indians than the atmosphere they breathed.” Tribal Trust Responsibilities The need to restore and maintain the natural production of anadromous fish in the Trinity River mainstem originates partly from the federal government’s trust responsibility to protect the fishery resources of the region’s tribes. The Trinity River Basin Fish and Wildlife Restoration Act of 1984 (Public Law 98-541) expressly acknowledges the tribal interest in the basin’s fishery resources by declaring that the measure of successful restoration of the Trinity River fishery includes the “ability of dependent tribal…fisheries” to participate fully through enhanced in-river “harvest opportunities, in the benefits of restoration.” In addition, the 1992 Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA) specifically recognizes the federal trust responsibility regarding the Trinity River fishery. The United States’ recognition of the importance of rivers and fish to the Indian people of the Klamath/Trinity Region is exemplified by the very shape and location of the lands first set aside for their reservations. In 1855, President Pierce established the Klamath River Reservation. The reservation (not to be confused with the Klamath Reservation in Oregon) was designated as a strip of territory commencing at the Pacific Ocean and extending one mile in width on each side of the Klamath River for a distance of approximately 20 miles. This reservation was created entirely within the aboriginal territory of the Yurok. On August 21, 1864, the U.S. Department of Interior (DOI) issued a proclamation and instructions that established the Hoopa Valley Reservation on the Trinity River pursuant to legislation enacted by Congress that same year. The reservation is 12 miles square and bisected by 15 miles of the river (it has often been called the Square or the 12-mile Square). In 1876 President Grant issued an Executive Order formally establishing the boundaries of the Hoopa Valley Reservation, and provided that the land contained within those boundaries “be withdrawn from public sale, and set apart in California by act of Congress approved April 8, 1864”. In 1891, President Harrison extended the Hoopa Valley Reservation from the mouth of the Trinity River to the ocean, thereby encompassing and including the Hoopa Valley Reservation, the original Klamath River Reservation, and the connecting strip between. By that time, as a result of the Dawes Act of 1887, much of the Klamath River Reservation and extension lands (the 20-mile strip that connected the two reservations is commonly referred to as the “Connecting Strip” or “Extension”) not already claimed as allotments by resident Indians had been opened up to non-Indian settlement. From 1891 through 1988, the Hoopa Valley Reservation was comprised of the Hoopa Valley Square, the Extension, and the original Klamath River Reservation. In 1988, Congress, under the Hoopa-Yurok Settlement Act, separated the Hoopa Valley Reservation into the present Yurok Reservation (a combination of the original Klamath River Reservation and Extension) and the Hoopa Valley Reservation. The map shown above identifies the current reservation boundaries. By first creating reservations “for Indian purposes,” the United States sought to provide the Hoopa Valley and Yurok Tribes with the opportunity to remain mostly self-sufficient, exercise their rights as sovereigns, and maintain their traditional ways of life. Implicit in this objective was an expectation that the federal government would protect the tribes and their resources (a protection that extended beyond reservation borders). The Unites States has a trust responsibility to protect tribal trust resources. In general, this tribal trust responsibility requires that the United States protect tribal fishing and water rights, which are held in trust for the benefit of the tribes. This trust responsibility is one held by all federal agencies. Reclamation is obligated to ensure that project operations do not interfere with the Tribes’ senior water rights. Pursuant to its trust responsibility and consistent with its other legal obligations, Reclamation must also prevent activities under its control that would adversely affect Tribal fishing rights, even when those activities take place off-reservation. Federally Reserved Indian Fishing Rights In most cases, federally reserved Indian fishing rights cannot be supplanted by state or federal regulation. The 1993 solicitor’s opinion: Today, the reserved fishing rights include the right to harvest quantities of fish that the Indians require to maintain a moderate standard of living, unless limited by the 50 percent allocation. Specifically, the tribes have a right to harvest all trust species of Klamath and Trinity River fish for their subsistence, ceremonial, and commercial needs. Tribal harvest of these species is guided by conservation requirements outlined in carefully developed tribal harvest management plans. GOLD! Discoveries in the late 1840s marked the start of drastic changes in the Trinity River and its watershed. Small–scale placer mining, like panning and sluicing, was mostly replaced by more efficient hydraulic and dredger mining by the early 1900s and continued through the 1950s. Historic Mining Activities, combined with reduced flows, had several negative impacts on the river, including: Major Pierson B. Reading discovered gold on the Trinity River near Douglas City in 1848 and within a year, the rich Trinity goldfields became the stuff of legend. Forty-niners poured into the area and on their heels came farmers, ranchers, shopkeepers, teamsters, and homesteaders. Settlements like Weaverville and Lewiston sprang up almost overnight and their connection to this major event can still be seen in the architecture along their main streets. After the gold played out and the prospectors moved on it was the farmers, ranchers and lumbermen who stayed on and became the economic mainstays of the area. Continued... Remnants from the California Gold Rush, in the form of dredger tailings piles, are visible up and down the Trinity River. Mary Smith was proprietor of the only woman-owned gold operation in all of California. Her mine was operational from the early 1900s to the early 1960s when it was shut down for construction of the Trinity and Lewiston Dams. By the 1950s, industrial logging began in earnest. In sensitive areas of the watershed, such as Grass Valley Creek, highly erodible granitic soils were left unprotected and large volumes of sand washed into the Trinity River (CDFG 1963). Prior to the construction of Trinity and Lewiston Dams, flooding negatively effected humans living along the Trinity River. During the winter of 1861-62, flooding wiped away most of the camps and communities living along the river’s flood path. On December 22, 1955, peak flows in the river reached an incredible 71,600 cfs, flooding most of downtown Lewiston once again. In 1955, the Trinity River Division of the Central Valley Project was authorized directing the construction of Trinity and Lewiston Dams, the Clear Creek Tunnel, Whiskeytown Dam, and a series of power plants. Completed in 1964, the Trinity River Division began a decades-long era wherein up to 90% of the inflow to Trinity Lake was exported from the Trinity River each year to support farming in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys. The Natural System The Trinity River’s native plants and animals are adapted to natural river flow patterns and habitat conditions. In the figure below, the annual life cycles of fall-run Chinook salmon and two riparian plants, black cottonwood and narrowleaf willow, are overlaid on an example natural hydrograph (a hydrograph shows the average flow for each day for every day of the year). Salmon adaptation to the river’s hydrology is evident — late fall and early winter rainstorms (the peaks in October through December) help draw adult salmon up into the river; winter baseflows allow for spawning; and the spring snowmelt (April through June) assists juveniles in their journey to the ocean before the warm, low flows of summer. Continued... The plants that live along the river are similarly adapted — winter rainstorms and spring snowmelt floods scour away dormant seedlings and saplings growing too close to the river’s edge. Seeds released in the spring and early summer sprout higher up on the bank when the water level is high; seedlings on these higher surfaces are able to grow during the slowly receding spring snowmelt, which recharges the groundwater table. Understanding these adaptations helps us evaluate the impact of river management and focuses our restoration actions on critical factors. The linkages between natural processes and biota are integrated in the Trinity River Restoration Program recommendations. TRD Impacts on the Trinity River A river’s size and shape (morphology) is determined by the interaction of its flows and sediment (fluvial processes). Prior to the TRD, streamflows varied greatly between and within each year. In a given year, flows could range from as low as 100 cubic feet per second (cfs) during the summer up to over 100,000 cfs during rare rain-on-snow floods. After the TRD was complete, flows were held between 150 cfs and 300 cfs year-round except for occasional storm-response reservoir releases, the largest of which was 14,500 cfs in 1974. The natural flow variability and sediment supply created a complex and dynamic channel which was beneficial to salmon and steelhead. However, when the TRD was completed, sediment (cobble, gravel, and sand) that had previously been supplied from the upper watershed was blocked from continuing down the river. The loss of sediment availability, and flow magnitude and variability, caused changes in the river channel downstream of Lewiston Dam. The most dramatic and obvious change was with riparian vegetation (the plants that live near the river). Under natural conditions, high winter and spring flows kept willows and alders from growing too close to the summer low flow channel (see photo below left). In the absence of high flows, these plants were able to sprout and become established in a thin band along the river’s edge (see photo below right). This dense vegetation traps sand, causing confining riparian berms to form. The berms, reaching up to 12 feet in height, act as levees to separate the river from its historic gravel/cobble bars and floodplains. TRD Impacts to Salmon and Steelhead Habitat Construction of the TRD effectively blocked 109 miles of anadromous rearing habitat upstream of Lewiston Dam. The changes to the Trinity River also altered the quantity and quality of habitat for salmon and steelhead below the dams. The habitat above the dams was entirely lost, and the remaining in-river habitat was severely degraded, especially from Lewiston Dam downstream to the North Fork of the Trinity River. Salmon and steelhead in the Trinity River depended on its dynamic and alluvial nature (mobile and free to form its bed and banks) for high quality habitat. Natural fluvial processes, driven by high flows and adequate coarse sediment supply, created and maintained complex channel morphology which provided suitable conditions for adults, eggs, alevin, fry, juveniles and smolts. After the dams, pools that were once deep and used by adult salmonids filled with sand. During summer, water temperatures reached lethal levels for juveniles and smolts, and gently sloping banks necessary for fry and juveniles were eliminated by riparian berms and much of the spawning gravel was scoured away. Remaining spawning gravel was choked with sand. Our increasing scientific understanding of the importance of natural river form and process to salmon and steelhead populations reinforces a recovery strategy that restores those natural conditions. How much have the Trinity River fish stocks declined? Prior to the dams, estimates of fish abundance were sporadic and imperfect. The best available estimates suggest that the number of fall-run Chinook salmon returning to the river each year varied between 19,000 and 75,500. Post-TRD, the average returns were approximately twenty percent of those estimates. In 1984, Congress passed the Trinity River Basin Fish and Wildlife Management Act (PL 98-541). This Act directed the Secretary of the Interior to develop a management program to restore fish populations to near pre-dam conditions. At that time it was thought that a goal of 62,000 natural (non-hatchery) fall-run Chinook salmon would maintain a healthy, sustainable population. The current Record of Decision does not specify numeric targets, but continues to strive for a naturally-spawning population at near pre-dam levels. Spring-run Chinook salmon, coho salmon and steelhead have shown similar declines. Coho salmon is also listed as a threatened species pursuant to the Endangered Species Act. RESOURCES FOR THE TRINITY RIVER

Continued...

SALMON IN THE TRINITY RIVER

NATIVE AMERICAN INFLUENCES

In the mid- to late-1800s, one of the primary purpose for establishing the reservations of the Hoopa Valley and Yurok Tribes, which are bisected by the Trinity and lower Klamath Rivers respectively, “was to secure to these Indians the access and right to fish without interference from others” in order to preserve and protect their right to maintain a self-sufficient livelihood from the abundance provided by the rivers (Memorandum from Solicitor to Secretary, Fishing Rights of the Yurok and the Hoopa Valley Tribes, M-36979, at 15, 18-21 (Oct. 4, 1993)).

The United States has a trust responsibility to protect and maintain rights reserved by, or granted to, federally recognized tribes and individual Indians, by treaties, statutes, and executive orders. Continued...

Salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, and lamprey that spawn in the Trinity River pass through the Hoopa Valley and Yurok Reservations and are harvested in tribal fisheries. The fishing traditions of these tribes stem from practices that far pre-date the arrival of non-Indians. Continued...

HISTORICAL INFLUENCES

DIVERSION IMPACTS